The year my oldest daughter was in fourth grade, we moved from a state that did not require end-of-year testing to Virginia, which did. That spring, her California Achievement Test (CAT) math scores showed she had an excellent understanding of math concepts but no ability to actually do computations. Her scores in those two areas were as far apart on the bell curve as they could get.

What did it mean?

At first, I was devastated. But looking more closely at the scores, I realized that my child had to have a learning disability. The difference between the two scores was too extreme. It indicated that there was something more going on than that I was a bad math teacher.

So, I reached out to my trusty friend, Google. I learned that my daughter’s difficulties with doing math on paper, the fact that she still, as a 9-year-old, wrote many numbers backward, and these odd scores, indicated she probably had a math learning disability called dyscalculia. She wasn’t being lazy, as some friends suggested, and I wasn’t a bad teacher. We just had to find a different way to do math.

Back to basics.

That summer, I decided we needed to go back to square one, learning to do math all over again. I started with addition.

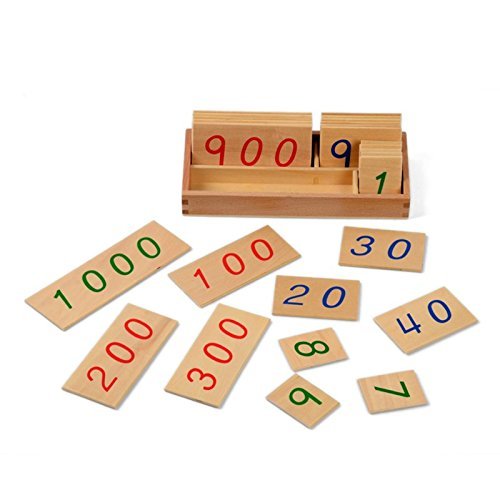

My daughter still struggled to write some numbers. So I got a set of wooden Montessori numbers and we did our problems with those. This took away the stress of writing the numbers, so we could focus on the math and the numbers conceptually.

My daughter still struggled to write some numbers. So I got a set of wooden Montessori numbers and we did our problems with those. This took away the stress of writing the numbers, so we could focus on the math and the numbers conceptually.

I started with simple problems I was pretty sure she could do. Day one we added two-digit numbers with no carrying, like 22+44. We also got out an abacus to help. The second day, we worked on adding two-digit numbers with carrying. This was hard for my daughter. But with the abacus, she could see the 10 beads that needed to be carried and moved them herself. For a while I helped, stepping back when I could see that she got the concept.

One day at a time.

Every day, we did math. We did only five problems a day so that our math time wasn’t overwhelming. If she struggled with the problems one day, we did more of the same type the next. Gradually, I changed from using the wooden numbers to doing our problems on a whiteboard, where it was easy to erase mistakes. However, I always let her use the wooden numbers or abacus if she wanted to. I never took those away.

After a week of two-digit numbers, we had a week of working with three-digit numbers. Then just a few days to learn four-digit numbers. By the end of the month, she could add a long string of numbers, with or without a decimal, and had moved on to putting that on paper. She felt proud of herself that math was finally making sense.

Taking it to the next level.

The second month, we started subtraction. I thought it would go much the same way as addition. But it was much harder for my daughter to get the hang of it. We once again got out the abacus and the wooden numbers and went at the pace my daughter needed, doing about five problems per session. Each day, if she was ready, the problems were just a tiny bit harder than the day before. I knew that if she felt successful, and not stressed, she would learn.

Subtraction took about twice as long to master as addition, but we got there. Using the abacus to understand borrowing was key, but it took more lessons and review than addition had.

Subtraction took about twice as long to master as addition, but we got there. Using the abacus to understand borrowing was key, but it took more lessons and review than addition had.

When we moved on to multiplication and, after that, division, I went to YouTube to watch videos of different ways to work problems. My daughter struggled with the long columns of numbers to add and subtract like I was taught. There were too many steps for her to memorize. Thankfully, YouTube has many videos of neat ways to multiply two-digit numbers and to do short division. Short division made sense to her in a way long division never did and she got the answers right!

Putting it to the test!

At the end of her fifth-grade year, my daughter once again took the CAT. Her math computation score was “above average!” In one school year, we had pulled her score up over 40 percentile points! I was so very proud of her. And I was proud of myself. I had worked hard that year to be the math teacher my daughter needed. Together, we did it. We stood up to the challenge of her dyscalculia and found a way to work through it and around it.

My daughter is now in high school and taking algebra. Math is not her favorite subject, by a long shot. She uses a calculator pretty liberally. And that’s OK. Almost as important to me as her math literacy we built that year was the confidence she and I built together. We know we can learn complex things, hard things that seem too just not make sense to us. All we need to do is break them down into smaller, more manageable pieces, and take our time. And that’s a lesson that will serve her well for life.

My daughter is now in high school and taking algebra. Math is not her favorite subject, by a long shot. She uses a calculator pretty liberally. And that’s OK. Almost as important to me as her math literacy we built that year was the confidence she and I built together. We know we can learn complex things, hard things that seem too just not make sense to us. All we need to do is break them down into smaller, more manageable pieces, and take our time. And that’s a lesson that will serve her well for life.

P.S. Here are the links to the different items I’ve recommended today.

|  | by Melissa & Doug | |

| for teaching place value |

** Our business does receive a small percentage of sales made through links on this page to Amazon as part of the Amazon Affiliates program and through links to Bookshop as part of the Bookshop Affiliates program. If you chose to purchase through one of these links, please know that we appreciate it. Thank you!

0 Comments